Meeting with Franz Thomastik |

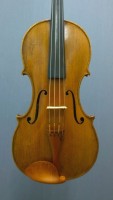

I am in the process of restringing my Ritter viola with Belcanto strings by Thomastik-Infeld.

Part of me loves the process, part of me despises it.

Ex-Rudolf Hindemith

I am happy for these are the only strings that fulfill my needs on this specific instrument. And I am unhappy about the strings being slightly too short to comfortably fit the 43cm mensur.

That's why I am using an extra long finetuner for the A string, and I have to open up the C string's wrapping by the peg box, so it fits. This kind of job doesn't always work out.

While I am immersed restringing my instrument, HE suddenly appears in the room. FRANZ THOMASTIK (1883-1951).

II recognize him, because I am currently in the process of reappraising a bequest including documents on his work. Firm, decisive stare, edgy eyes, big nose, high forehead, woolly hair, large sideburns, and ears that look like they can hear into far distances...

Author (A): This isn't real, you have entered the realm of the death longtime ago!

(1883-1951)

Franz Thomastik (FT): Oh well, death is just the big grother of sleep. A human being stays alive in people's heads.

A: That's true. Your name THOMASTIK is of global format - well, not everybody knows - however all string players. THOMASTIK strings: Spirocore, precision, artist-rope, strings, dominant, vision, belcanto, pi...

FT: Ah yes, the strings... It is nice to see that my name has survived together with them. Sadly though, they were only a small part of my company's universe.

A: How do you mean that?

FT: I was always driven by sound. The distant sound, unfindable on earth. By the end of the 19th century, the world had come to a halt in every regard. Politically, economically, culturally. Decadence everywhere...

A: Tell me more! How did you come to your findings? In the meantime we've advanced another 150 years, and it seems to feel pretty good...

FT: Careful, my friend! Looking down to earth, I can tell you that there's a shift happening, similar to the one in the 1920s. Keep your eyes open!

A: How do you mean?

A: How do you mean?

FT: The 1920s. Everything seemed possible. Nobody was interested in limits after WW1. Mechanical music started its triumphal march. Grammophon, radio, sound film. All of it was steadily accessible. Now imagine: In Vienna! Poorly attended concert venues. Unemployed musicians on the streets and alleys. As of today, YOU are in a digital shift. That is ten times worse. Everything is available 24/7, yet seems to lack life and soul.

A: True, however there's an uptrend in today's concert life. People say that every year there's more concertgoers than people seeing the national league.

FT: And what do they listen do? Old music. Classical, romantic repertoire. Beethoven, Brahms, Tchaikovsky.

A: Is that a bad thing?

FT: Not too bad, but old fashioned. Just imagine the music we'd be able to hear, if these unspeakable wars hadn't taken place?! Particularly WW2. The eradication of Jewish culture, people and thinking, which despite everything was «German» in the best sense. People were sawing off their own branch!

A: Please keep talking for as long as I can see you. It seems like you just got started.

FT: With good reason. The wars didn't just take everything from me, but also almost completely deprived the coming generations of my impulse. (Musing) We might be mostly listening to so called «contemporary» music on «contemporary» instruments, if we'd been spared of the global conflagration...

A: Contemporary instruments? Are you talking of electric instruments?

coworkers

FT: Please don't mention it! Now, let's start from the beginning:

I was born in 1883 in Holleschau/Mähren, which today is Holesov in the Czech Republic. Where is that? Nobody knows that nowadays. In 1941, the Nazis knew that we had the largest Jewish community in Mähren, which is why they set the wonderful synagogue on fire. Wagner dies in 1883, leaving a huge construction of sound, both literally and metaphorically. Smetana dies the following year. Tchaikovsky in 1893 etc.

Richard Strauss starts his career. Music could only be experienced by visiting concerts or playing on your own. My home home isn't as rural as some of you might think. A wonderful Baroque castle and churches are evidence of great culture, still as of today.

FT: As a kid I was always impressed by the dancing violinists, which played on the weekends. I asked my father, a grocer and soap maker, to buy me a violin. I was 5. «Then go build yourself one», was his discouraging - or rather highly motivating - answer.

«Build yourself one» became my life philosophy.

A: So you became a violin maker?

FT: Not at first. That was too simple. Bigger thoughts were under the table. First I studied philosophy and physics in Vienna. I received my doctorate in 1908. The whole world was changing. Politically: Rejecting the emperor, moving towards democracy. Economically: Industrial revolution. Culturally: Freedom, e.g. moving away from tonality...

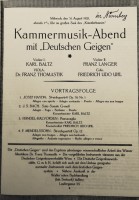

Karl Weidler

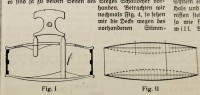

The Italian violins were built in a time, when the earth was still seen as flat: A cover made of spruce wood, vibrating through the small wooden bridge. At the same time, a rod inside (wrest plank) the free vibration. The system was used to its full extent. New elements had to be found and invented. The sound needed to be able to depict the universe. Reaching up to the stars. Combining their power. That's the path the wind instruments walked in the 19th century. The string instruments came to a halt in 1650.

A: How did you proceed further?

FT: In 1908 I got in touch with an anthroposophic movement. Rudolf Steiner held presentations in Vienna. A charismatic human, whose findings in human science have remained uncontested as of today. We met personally, became lifelong friends and conversed about musical questions, as well as the threefold division of the social system.

A: And the sound, the violins??

FT: Everything needed to build on solid craftmanship. Fictional philosophing in one's head wasn't believable. At first I went to Markneukirchen, then to Mittenwald, to learn in the centers of violin making.

Still before WW1, I opened my own violin building shop in Vienna. A dream came true. I could work.

A: That means?

FT: Maple, spruce. Maple, spruce, the same for centuries.

FT: Maple, spruce. Maple, spruce, the same for centuries.

There were other woods too: Oak, beech, ash-tree, birch, elm etc. Every tree summons other planetary forces to the earth.

Each voice in a string quartet is given its own wood, its uniqueness. An instrument made completely of one wood type:

1. violin maple

2. violin cherry

3. viola birch

4. cello ash-tree

Puncturing of the cover. A tailpiece on the cover, one on the bottom. Bottom and cover start resonating.

From resonating body to organism.

Extension of the string family to seven instruments. An additional treble violin, a tenor cello, closing the gap between viola and cello, and a contra bass made from white beech. This family represents the seven planetary forces similarly to the pillars of the first Goetheanum.

A: Slow down please, I can barely keep up with you.

FT: It was a big part of history. Better said, it IS a big part of history. Why do you complain, isn't it an ash-tree viola you play?!

A: Why do you know...?!

Yes! 25 years ago, I heard the string septet Heiligenberg (fixed formation) play in Dornach, at a concert in the Goetheanum. An unforgettable experience. Arthur Bay completed your impulse, building all seven instruments. After that, I really wanted such an ash-viola.

FT: (contemplative, sad) These damn wars!

During WW1 I was called to the front. My leg was shot up. Disability and pain followed. After the war we continued. We «Thomastik and employees», including Otto Infeld, Ludwig Kremling, Hans Lessmann, Alois Ratzmann and Karl Weidler.

A: A manufactory?

FT: That too. More of a merger of likeminded people, confirming each other's paths.

FT: That too. More of a merger of likeminded people, confirming each other's paths.

1933 was the darkest time. We couldn't ship any strings to Germany anymore. We had reinvented the wheel with our wound steel strings. The catgut didn't do justice to modern virtuosity and sound requirements. Surprisingly, our strings were a much bigger success than our new instruments, and they still are.

If I am seeing right, you are using Thomastik strings right now, correct?

A: I hesitate: I've completely forgotten what I've been doing. Just listening to my unexpected guest, asking question after question for as long as I perceive HIM.

Economic sanctions on strings?

FT: Absolutely! It seems you're repeating the same nonsense now, 100 years later! «Brotherhood»! You're taking your distance of it quickly.

Now, we solved the problem by having our friend Karl Weidler returning to Nürnberg. There we built a branch for the German market. It didn't last long. In 1944, both manufactories, in Vienna and Nürnberg, were bombed down. Everything was destroyed: instruments, blueprints, rare materials, wood, varnish and rosin...

All gone!

(Ex-Renate Schmidt)

With what was left from our wills, we started again in 1949 in the Mollardgasse 84A in Vienna.

LUDWIG KREMLING started creating rosin and metal additives. We needed a suitable rosin for our steel strings and our theory of the planets. Each sound needs its wood and rosin.

It was the beginning of the rosin, which you can now buy in its third generation as «Neues Liebenzeller Metallkolophonium» and as «Larica». It is one of the most popular rosins worldwide! In 1950, OTTO INFELD took over the production of the strings as his own company.

Still as of today, THOMASTIK-INFELD is one of the two big players in the string business, worldwide.

In 1951 I said goodbye to my friends with the words: «Live as you can. However, live and work so that people believe you, when you're talking about spiritual miracles.» I died on the 19th of November, 1951.

The development of the strings progressed at a fast pace. I believe that the steel core would be it.

A: As of today, synthetic cores of all kind are in demand. They combine the balance of a steel structure with the warmth and response of catgut strings.

FT: sighs...

A: Don't leave me right now!

I mean to write a blog for a viola column. You, Thomastik and the viola. Tell me more!

Franz Thomastik

FT: (eyes lighten up)

I loved the viola, played it myself in the «Thomastik-Quartet». Carl von Baltz from the Wiener Symphoniker was our first violinist. The audience was delighted wherever we played. Imagine, in a time when Hindemith traveled with his quartet! Strauss writing his last opera. The last signs of live of the Art Nouveau style. I could exchange thoughts with Rudolf Steiner, personally.

He said: «The old violins have a warmth, just as if one was lying in bed, and your violins have a warmth as is the sun was rising.»

BOOM! A BANG!

Lost in thoughts over the encounter, I kept tightening the A string, which now burst with a loud noise. Merde! - Thanks God, I have another one...

The manifestation has disappeared. Emptiness fills the room.

It takes 120 years for an oak to be usable for furnite construction.

It took 130 years for Hermann Ritter's three-legged bridge to experience a renaissance.

It probably won't take long now, until violin maker Franz Thomastik's impulse is picked up again.

I know of two violins. One survived in the Reka collection of the museum Viadrina in Frankfurt/Oder. The other one (Ex-Renate Schmidt) is part of the Goetheanum collection in Dornach/CH.

Even though Rudolf Steinger predicted great resistance to Franz Thomastik, it was worth resisting, and to explore a still young universe of sound.

This blog article was written by Martin Hahn, a versatile musician (Violist), pursuing various paths in his career. The most important one is his job with the Badische Philharmonie Pforzheim, the orchestra that accompanies all performances of the Musiktheater am Stadttheater Pforzheim, Germany.

Photos: Martin Hahn, 2018

|

Write an input |

2. Find the composer or work for which you want to write an input.

3. On the right side: click on «Write an input».

Pseudonym

Your input will only be published under your pseudonym. Under «My account» you can enter your pseudonym at any time.

| Out of our online shop |

Zwei Sonaten for Viola solo and Cello

in the St. Hilarius Church in Näfels, Switzerland

6 Sonatas for 2 violas

| You may also be interested in |

The literature described in his epochal viola guide «Music for Viola» has all been played, described on index cards and archived by Konrad Ewald himself. Most of it is, or was, in his possession and is neatly arranged and filed.

» To the viola blog

Where it all began...

Violist Martin Hahn is a versatile musician, pursuing various paths in his career. The most important one is his job with the Badische Philharmonie Pforzheim, the orchestra that accompanies all performances of the Musiktheater am Stadttheater Pforzheim, Germany.

» To the viola blog

Rediscovered composer: Alexander Presuhn

As music director of the theatre, he has not only arranged and composed about 50 music for the stage, but as composer he has also written numerous works for and with «his» instrument, the viola.

» To the viola blog

Research Topic Viola Music

The musicologist Phillip Schmidt has dedicated himself to 18th century viola music. Schmidt originally wanted to become a singer or chemist, but then decided to pursue a career in musicology. He pays special attention to the viola, his favourite instrument, which he also plays himself.

» To the viola blog

Viola letter |

Do you don't want to miss any news regarding viola anymore? Our viola letter will keep you informed.

Do you don't want to miss any news regarding viola anymore? Our viola letter will keep you informed.» Subscribe to our viola letter for free

|

|

Visit and like us on Facebook.

Visit and like us on Facebook.» Music4Viola on Facebook